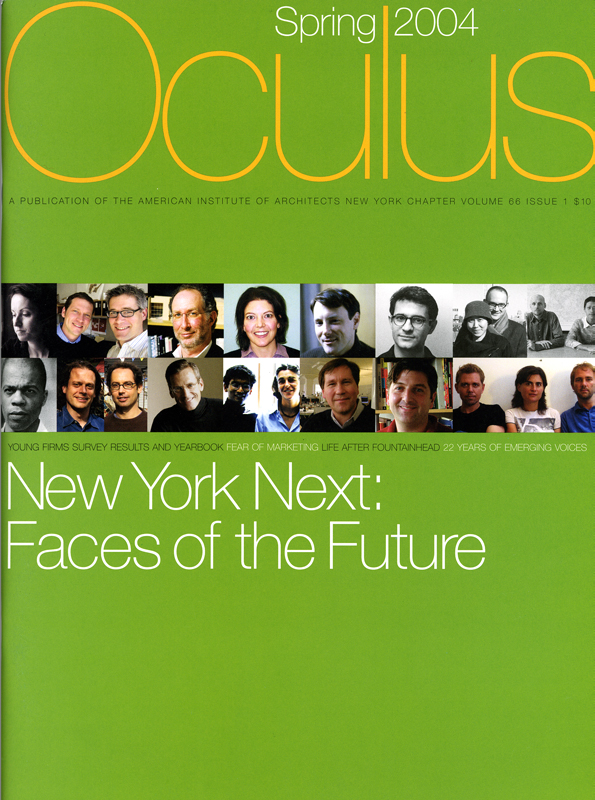

Oculus

“Life After Fountainhead.” Young, Robert. Spring 2004.

see project page for Bluff House and Montauk Lake House

see project page for Bluff House and Montauk Lake House

As architects, we work alone through the night at our drafting tables, geniuses creating great buildings through skill, talent, and sheer willpower. In return, we are rewarded with glory, wealth, and most importantly, total control over our projects.

Pure fantasy, right? By all rights, this cliché image of the architect as lone-hero should be dismissed out of hand, not only as wrong, but also as a danger to our profession. To begin with, architects can't function as a team of one, and the fantasy that we can just lures more egomaniacs into the fold. But what does it mean to be an architect?

When I was a kid, I wanted to be an architect the way other kids wanted to be firemen. I saw things in idealistic and heroic terms. After practicing architecture for a few years, the fantasy has unraveled a bit, but there still seems to be something worthwhile there. I may have been duped by the image of the lone ranger with a T-square, but maybe that's not such a bad thing.

I brought my naive conception of the profession to architecture school, where it was welcomed and reinforced. Sure, we talked about the "Death of the Author" and snickered at Ayn Rand's depiction of Howard Roark, Architect, in theory class, but it was in studio that I learned to pull all-nighters and win praise from a jury for designs that I had conceived and refined to a slick perfection all alone. After graduating from architecture school, I had no reason to think being an architect wouldn't reflect the simplistic vision I had formed as a kid and found confirmed as a student.

As an intern fresh out of the Tulane School of Architecture, I never had a problem with doing the drudgework all interns must do, but I was confused by the ambiguity of my role in the larger process of making buildings. The first thing I learned was that my own performance was not the only factor in success or failure of a building, and that my contribution could not be isolated and evaluated the way it could in academia.

In the small design firms where I worked, I sought more and more responsibility and control over the jobs I worked on. When I became a Project Architect, I thrived on seeing each project through from start to finish. Increasing my contribution to a project reduced the ambiguity, and brought me closer to my conception of the architect as the center-of-the-universe.

There was no cathartic moment when I woke up and declared: "This is a crock!" But my day-to-day experience was proving my idea of an architect to be flawed. Working with clients, contractors, my bosses, and others to get a building built turned out to be a dynamic process of give and take that bore little resemblance to what I had imagined and even less to the simple exercises in design studio. After five years of architecture school, and three years of internship, my "education" had barely started. I had graduated from kindergarten.

One reason I enjoyed working in small design firms was that most of the action takes place in a single room, so I was learning not just about my projects, but all those around me. At the same time, I wondered: How does the work I am doing as a designer and project architect relate to the "business" of being an architect?

When I was in my mid-twenties, I faced a choice: continue to work in a firm (paycheck and apprenticeship), go back to graduate school (debt and abstraction), or start my own firm (trial by fire).

I decided to hang out my shingle because I figured that the experience of starting a firm would teach me more than my elders in a firm or school could. Plus, I wanted to be "the boss" and find out for myself how a firm really works. My first discovery was that despite owning the business, I wasn't the boss at least not in the way I had anticipated. The boss, I quickly discovered, is a multi-headed hydra beast: each head is a boss, and there are as many bosses as there are clients, employees, consultants, contractors, accountants, and attorneys. My job was not to "boss"; it was to steer this unruly pack toward a common goal.

Another cliché is that architects are hopeless when it comes to business, but there is a parallel between managing an architectural project and managing a business. In both cases, our contribution is not necessarily to control and master every facet of the process, but to bring the far-flung and often conflicting aspects of the enterprise into a cohesive vision. For me, it took being a principal of a newly minted architecture firm to really get that - I was suddenly an architect and a businessman. No longer was I the project architect whose sole responsibility was the success of the project. I now had the success of the firm to strive for, which meant we had to stay in business.

At first, I worked out of my apartment and set the goal of paying my rent with only real commissions - no freelancing for other architects. Then, when I found a small studio space for rent, my goal was to pay two rents. Later, when I hired my first employee, it became three rents I had to support, and so on. Perhaps the mortal blow to my conception of the lone architect was when I realized that I could not do it all alone and invited my longtime friend and colleague Shea Murdock, AlA, to join me in a partnership of equals, forming Murdock Young Architects in 1999. The partnership is based on the idea that we could do more together than the sum of what either of us could do alone.

The cliché image of the solo-architect was part of my motivation to go out on my own, but it was the experience of running a firm that showed me firsthand that architecture is not a solo endeavor.

So what is an architect, if the cliché is a fantasy? Truth and fantasy are raveled so tightly together, I'm not sure they can be separated. The heroic aspect of our self-image is more than our inflated egos; it is also our idealism inspiring us to invest ourselves in a way that is not justified by the tangible rewards.

As architects, we put in the late nights, dream up new buildings, fret over details, balance the books, and stick our necks out for the greater vision of each project because we love architecture and because we will always see ourselves to some extent as heroes fighting for a cause greater than ourselves.

Murdock Young Architects, formed by Robert Young, AlA, and Shea Murdock, AlA, in 1999, is a studio of six architects based in Manhattan and Montauk, New York.

Pure fantasy, right? By all rights, this cliché image of the architect as lone-hero should be dismissed out of hand, not only as wrong, but also as a danger to our profession. To begin with, architects can't function as a team of one, and the fantasy that we can just lures more egomaniacs into the fold. But what does it mean to be an architect?

When I was a kid, I wanted to be an architect the way other kids wanted to be firemen. I saw things in idealistic and heroic terms. After practicing architecture for a few years, the fantasy has unraveled a bit, but there still seems to be something worthwhile there. I may have been duped by the image of the lone ranger with a T-square, but maybe that's not such a bad thing.

I brought my naive conception of the profession to architecture school, where it was welcomed and reinforced. Sure, we talked about the "Death of the Author" and snickered at Ayn Rand's depiction of Howard Roark, Architect, in theory class, but it was in studio that I learned to pull all-nighters and win praise from a jury for designs that I had conceived and refined to a slick perfection all alone. After graduating from architecture school, I had no reason to think being an architect wouldn't reflect the simplistic vision I had formed as a kid and found confirmed as a student.

As an intern fresh out of the Tulane School of Architecture, I never had a problem with doing the drudgework all interns must do, but I was confused by the ambiguity of my role in the larger process of making buildings. The first thing I learned was that my own performance was not the only factor in success or failure of a building, and that my contribution could not be isolated and evaluated the way it could in academia.

In the small design firms where I worked, I sought more and more responsibility and control over the jobs I worked on. When I became a Project Architect, I thrived on seeing each project through from start to finish. Increasing my contribution to a project reduced the ambiguity, and brought me closer to my conception of the architect as the center-of-the-universe.

There was no cathartic moment when I woke up and declared: "This is a crock!" But my day-to-day experience was proving my idea of an architect to be flawed. Working with clients, contractors, my bosses, and others to get a building built turned out to be a dynamic process of give and take that bore little resemblance to what I had imagined and even less to the simple exercises in design studio. After five years of architecture school, and three years of internship, my "education" had barely started. I had graduated from kindergarten.

One reason I enjoyed working in small design firms was that most of the action takes place in a single room, so I was learning not just about my projects, but all those around me. At the same time, I wondered: How does the work I am doing as a designer and project architect relate to the "business" of being an architect?

When I was in my mid-twenties, I faced a choice: continue to work in a firm (paycheck and apprenticeship), go back to graduate school (debt and abstraction), or start my own firm (trial by fire).

I decided to hang out my shingle because I figured that the experience of starting a firm would teach me more than my elders in a firm or school could. Plus, I wanted to be "the boss" and find out for myself how a firm really works. My first discovery was that despite owning the business, I wasn't the boss at least not in the way I had anticipated. The boss, I quickly discovered, is a multi-headed hydra beast: each head is a boss, and there are as many bosses as there are clients, employees, consultants, contractors, accountants, and attorneys. My job was not to "boss"; it was to steer this unruly pack toward a common goal.

Another cliché is that architects are hopeless when it comes to business, but there is a parallel between managing an architectural project and managing a business. In both cases, our contribution is not necessarily to control and master every facet of the process, but to bring the far-flung and often conflicting aspects of the enterprise into a cohesive vision. For me, it took being a principal of a newly minted architecture firm to really get that - I was suddenly an architect and a businessman. No longer was I the project architect whose sole responsibility was the success of the project. I now had the success of the firm to strive for, which meant we had to stay in business.

At first, I worked out of my apartment and set the goal of paying my rent with only real commissions - no freelancing for other architects. Then, when I found a small studio space for rent, my goal was to pay two rents. Later, when I hired my first employee, it became three rents I had to support, and so on. Perhaps the mortal blow to my conception of the lone architect was when I realized that I could not do it all alone and invited my longtime friend and colleague Shea Murdock, AlA, to join me in a partnership of equals, forming Murdock Young Architects in 1999. The partnership is based on the idea that we could do more together than the sum of what either of us could do alone.

The cliché image of the solo-architect was part of my motivation to go out on my own, but it was the experience of running a firm that showed me firsthand that architecture is not a solo endeavor.

So what is an architect, if the cliché is a fantasy? Truth and fantasy are raveled so tightly together, I'm not sure they can be separated. The heroic aspect of our self-image is more than our inflated egos; it is also our idealism inspiring us to invest ourselves in a way that is not justified by the tangible rewards.

As architects, we put in the late nights, dream up new buildings, fret over details, balance the books, and stick our necks out for the greater vision of each project because we love architecture and because we will always see ourselves to some extent as heroes fighting for a cause greater than ourselves.

Murdock Young Architects, formed by Robert Young, AlA, and Shea Murdock, AlA, in 1999, is a studio of six architects based in Manhattan and Montauk, New York.