Interior Design

“Strip Search.” Geran, Monica. January 1999.

see project page here

see project page here

EVEN BEFORE SETTING their wedding date, Suzanne Crowe, a television producer at J. Walter Thompson (the advertising agency, of course) and Gavin Cutler, partner at MacKenzie Cutler (commercial film editing), bought a 2,500-sq.-ft./ bi-level loft in Manhattan's South Street Seaport area. The venue, an eight-floor industrial structure built at the turn of the century, had been converted in the late 1970s; as for the flat of choice, at the indiscretion of former inhabitants, it underwent ill-advised updating shortly thereafter. But the good bone structure showed through the maquillage, an omen of promise to architect/ interiors expert Robert Young, who, having at one time done some office design for Cutler, was to become the man in charge. The clients-to-be, kindred spirits both, agreed with Young's assessment and soon turned into active collaborators in developing the basic design.

Reminders of prior occupancy were plentiful. Found among them were full-floor carpeting creeping partway up the wall; erratically varied floor levels; scads of partitions paved with ungainly vinyl; blocked-out window views-need one say more? And yet, recalls Young, he couldn't stop believing that the beautiful shell beneath was begging to be fully exposed. Its presence, he sensed, was needed to reinforce the link between the structural ingredients-concrete, brick, varied woods, steel beams, and more-to the "gritty urban context" outside. But just to make sure that there'd be no disappointments once the demolition process had begun, the architect did some excavating, using a hammer to test the ceiling where, eureka, he found a fine now-exposed beam and evidence of vaulted roofing. From these findings arose the mutually endorsed plan: that the shell would be restored to its original condition and, thereafter, budgeted money, instead of being stretched too far, would be invested mainly on the upper (6th) floor so as to turn it into something quite spectacular. Some work on the level below has been shelved for an envisaged Phase II. In the interim, the private spaces there were only mildly modified and then furnished in fashionable makeshift style.

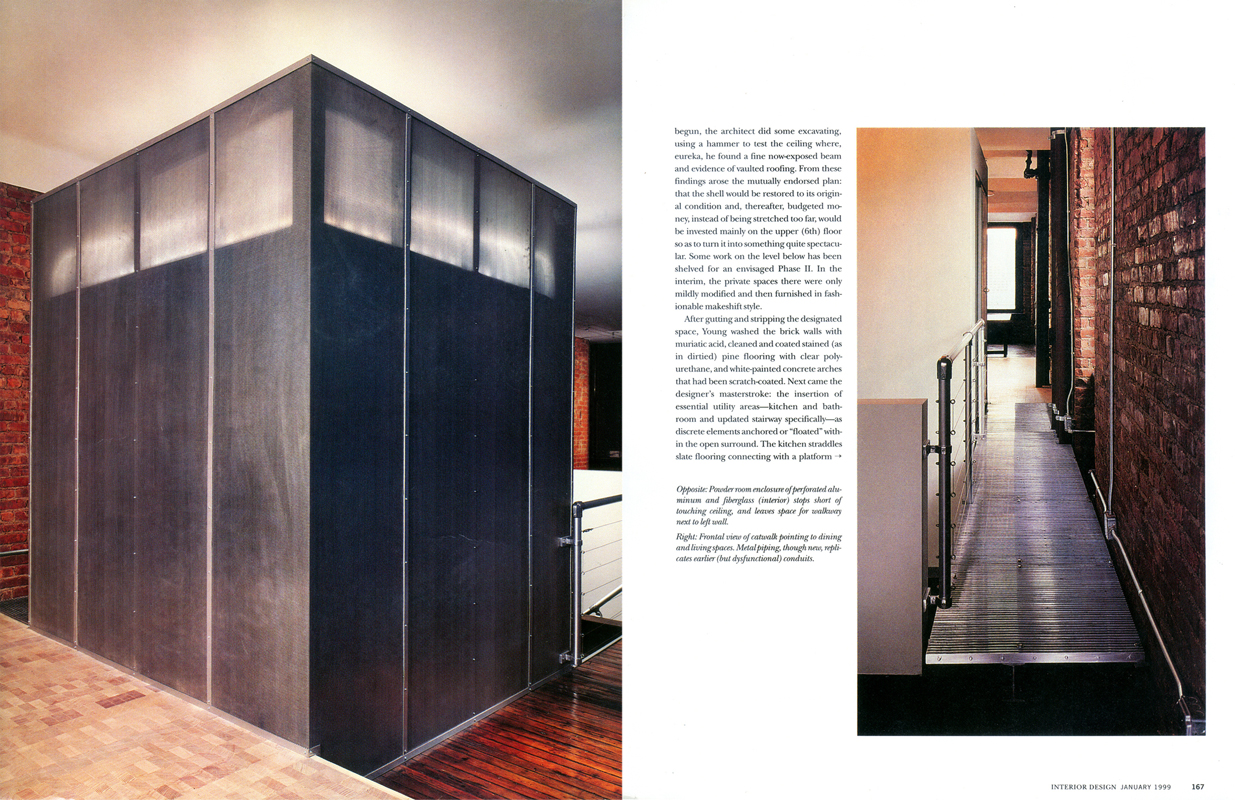

After gutting and stripping the designated space, Young washed the brick walls with muriatic acid, cleaned and coated stained (as in dirtied) pine flooring with clear polyurethane, and white-painted concrete arches that had been scratch-coated. Next came the designer's masterstroke: the insertion of essential utility areas-kitchen and bathroom and updated stairway specifically-as discrete elements anchored or "floated" within the open surround. The kitchen straddles slate flooring connecting with a platform of end-grain block fir; the rest of the cookery/dining area appears to sit atop heart pine planking. Immediately across the entry, an extant stairwell was widened after its three-steps-up base had been downsized, making room for the enlarged opening next to the steps; above, an aluminum catwalk caps one side of the opening. Components come from the proverbial kit-of-parts; stainless steel cables are threaded through eyelets attached to uprights and tightened with turnbuckles. About the grilled walkway atop, Young admits that it was a bit of a folly irresistible as a way of celebrating height.

Materials and forms of custom-made furniture and companion appointments are replays of, or compatible with, the built envelope. Examples are perforated aluminum panels as a wrap-up for the powder room (lined, in turn, with fiberglass), maple cabinetry, walnut dining table, glass and mosaic tiles, and more. (Upholstered seating had not as yet been installed at time of photography.) This writer's favorite by far is Young's eye-catcher washbasin: inspired by fanciful and unaffordable models found in exclusive showrooms, he bought (for $20, at a used bicycle shop) a bare wheel-rim and dropped a stainless steel bowl into it. Dark metal legs were made to order; all other members came off shelves. Result: Simply fab.

Low-voltage ceiling lights are kept afloat via tensed cables holding tiny halogen fixtures. In vaulted sections, dark metal tension rods hold together arches. And as if to make amends for the erstwhile shutout of views, glass shelving of kitchen cabinets at the central window's vantage point are placed so that the Brooklyn Bridge can be seen in all its unobstructed glory. About seven months passed between client meeting and job completion. Collaborating throughout was Joel Shifflet.

Reminders of prior occupancy were plentiful. Found among them were full-floor carpeting creeping partway up the wall; erratically varied floor levels; scads of partitions paved with ungainly vinyl; blocked-out window views-need one say more? And yet, recalls Young, he couldn't stop believing that the beautiful shell beneath was begging to be fully exposed. Its presence, he sensed, was needed to reinforce the link between the structural ingredients-concrete, brick, varied woods, steel beams, and more-to the "gritty urban context" outside. But just to make sure that there'd be no disappointments once the demolition process had begun, the architect did some excavating, using a hammer to test the ceiling where, eureka, he found a fine now-exposed beam and evidence of vaulted roofing. From these findings arose the mutually endorsed plan: that the shell would be restored to its original condition and, thereafter, budgeted money, instead of being stretched too far, would be invested mainly on the upper (6th) floor so as to turn it into something quite spectacular. Some work on the level below has been shelved for an envisaged Phase II. In the interim, the private spaces there were only mildly modified and then furnished in fashionable makeshift style.

After gutting and stripping the designated space, Young washed the brick walls with muriatic acid, cleaned and coated stained (as in dirtied) pine flooring with clear polyurethane, and white-painted concrete arches that had been scratch-coated. Next came the designer's masterstroke: the insertion of essential utility areas-kitchen and bathroom and updated stairway specifically-as discrete elements anchored or "floated" within the open surround. The kitchen straddles slate flooring connecting with a platform of end-grain block fir; the rest of the cookery/dining area appears to sit atop heart pine planking. Immediately across the entry, an extant stairwell was widened after its three-steps-up base had been downsized, making room for the enlarged opening next to the steps; above, an aluminum catwalk caps one side of the opening. Components come from the proverbial kit-of-parts; stainless steel cables are threaded through eyelets attached to uprights and tightened with turnbuckles. About the grilled walkway atop, Young admits that it was a bit of a folly irresistible as a way of celebrating height.

Materials and forms of custom-made furniture and companion appointments are replays of, or compatible with, the built envelope. Examples are perforated aluminum panels as a wrap-up for the powder room (lined, in turn, with fiberglass), maple cabinetry, walnut dining table, glass and mosaic tiles, and more. (Upholstered seating had not as yet been installed at time of photography.) This writer's favorite by far is Young's eye-catcher washbasin: inspired by fanciful and unaffordable models found in exclusive showrooms, he bought (for $20, at a used bicycle shop) a bare wheel-rim and dropped a stainless steel bowl into it. Dark metal legs were made to order; all other members came off shelves. Result: Simply fab.

Low-voltage ceiling lights are kept afloat via tensed cables holding tiny halogen fixtures. In vaulted sections, dark metal tension rods hold together arches. And as if to make amends for the erstwhile shutout of views, glass shelving of kitchen cabinets at the central window's vantage point are placed so that the Brooklyn Bridge can be seen in all its unobstructed glory. About seven months passed between client meeting and job completion. Collaborating throughout was Joel Shifflet.